ALONG THE CANAL D'OURCQ: A Drawing Walk, made as part of the Banlieue Network Summer School, July 2013

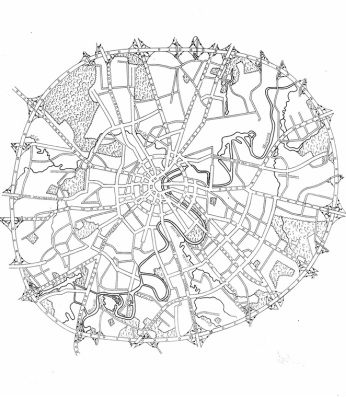

The shape of the city eludes you; the pursuit of an idea of the banlieue is not as simple as marking a frontier dividing inner from outer, urbanity from the suburban. Nevertheless maps offer us something to work with – a delimitation if only as something to resist. In approaching a city, the map, held in the hand or in the mind’s eye, offers a way to begin, to set forth on the city. This mental shape of the city is fundamental; the convulsed intestine sprawl of London’s Thames, Moscow’s wobbly bicycle wheel of encircling boulevards and ring roads, the grids of Glasgow and Chicago. On these abstracted patterns we inscribe our course, charting a route through the interior or walking the perimeter, the encircling walls or their modern replacements – ring roads and raised motorways. The desire to encompass the city is a sort of will for possession, as though by walking a circumference one might physically contain the interior and its varied secrets, an attempt by holding the outskirts, to put oneself at the centre of the city’s space. Perhaps these heroic pedestrian perambulations become more urgent as cities sprawl and map themselves for cars and transport not for walkers; a marking or drawing out on foot as a way of understanding.

Artists have often sought the outskirts, the city’s limits, in an attempt at nudging out some sort of truth about the fast changing existence within; thus in Paris, Seurat’s drawings of The Zone beyond the city walls of the 1880s, the paintings made at the edge of the city by Pissarro and Van Gogh, Lowry’s walks and depictions of the declining industrial landscapes on the edges of Salford and Manchester and Yeats’ sketches of Dublin’s periphery made in the emerging Irish free state. Last summer, it was proposed to take a group of urban researchers for a drawing walk, carrying pencils and sketchbooks, combining walking, looking and drawing. We chose a route along the Canal d’Ourcq, the limits of the city proper, under the bridge of the Périphérique, to surface at Bobigny.

Many of the participants were new to this territory, at least on foot, and new to drawing. I try to explain about drawing, like walking, being a way to find a new rhythm of observation; a way to pause and to watch, to gather information, but very differently to the modes of academic field research. Drawing on the spot is more passive to that which arrives, it does not propose; it is a sort of listening in. The drawing line is a line thrown out to the unknown, you keep it going, waiting for something to happen within the space.

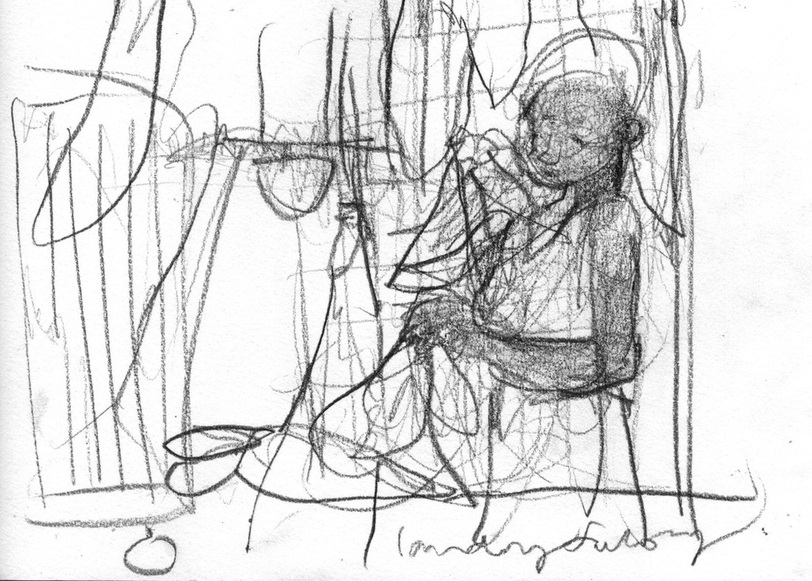

Our first pause is just under a large bridge, where the Périphérique thunders over us. Underneath the bridge it is still and quiet – a sudden darkness after the intense heat of this dog day afternoon. People are drawn in by lines of washing, hanging in the last patch of sun before the bridge’s heavy canopy. They stop to look and to draw - it is an instantly appealing thing to put on paper and we pause there looking and drawing. Only later we notice a man trying to shuffle through us unnoticed, trying to carry on his work of hanging out washing – only then do we realise the significance of our setting; that underneath the arch of the bridge is a makeshift gate walling in the space from the embankment down to the canal side path, and that behind that gate are private homes, an encampment, and that we are standing here in their laundry room, and that this man is trying to continue the intimate business of his washing. Discreetly, he shifts his plastic stool and bucket to the far side of the bridge where he can continue his work undisturbed. I try and note his presence in my sketchbook without being seen, before the group moves on. A bicycle flashes past, people move past him but he sits separate, mostly unobserved, concentrated in the space of his bucket, the water, the cloth; pouring out the old suds into the canal and lowering the bucket back in to fill it up. After washing the cloths he proceeds to wash his hands and then his feet. There is an intimacy about this activity that, while it is exactly the sort of gift we are waiting for in our search, is also an embarrassment, it feels intrusive. The man’s quiet discretion, his maintenance of privacy in the face of this crowd of unforeseen observers makes us seem awkward, ungainly in our fumbling pursuit of his secret.

Many of the participants were new to this territory, at least on foot, and new to drawing. I try to explain about drawing, like walking, being a way to find a new rhythm of observation; a way to pause and to watch, to gather information, but very differently to the modes of academic field research. Drawing on the spot is more passive to that which arrives, it does not propose; it is a sort of listening in. The drawing line is a line thrown out to the unknown, you keep it going, waiting for something to happen within the space.

Our first pause is just under a large bridge, where the Périphérique thunders over us. Underneath the bridge it is still and quiet – a sudden darkness after the intense heat of this dog day afternoon. People are drawn in by lines of washing, hanging in the last patch of sun before the bridge’s heavy canopy. They stop to look and to draw - it is an instantly appealing thing to put on paper and we pause there looking and drawing. Only later we notice a man trying to shuffle through us unnoticed, trying to carry on his work of hanging out washing – only then do we realise the significance of our setting; that underneath the arch of the bridge is a makeshift gate walling in the space from the embankment down to the canal side path, and that behind that gate are private homes, an encampment, and that we are standing here in their laundry room, and that this man is trying to continue the intimate business of his washing. Discreetly, he shifts his plastic stool and bucket to the far side of the bridge where he can continue his work undisturbed. I try and note his presence in my sketchbook without being seen, before the group moves on. A bicycle flashes past, people move past him but he sits separate, mostly unobserved, concentrated in the space of his bucket, the water, the cloth; pouring out the old suds into the canal and lowering the bucket back in to fill it up. After washing the cloths he proceeds to wash his hands and then his feet. There is an intimacy about this activity that, while it is exactly the sort of gift we are waiting for in our search, is also an embarrassment, it feels intrusive. The man’s quiet discretion, his maintenance of privacy in the face of this crowd of unforeseen observers makes us seem awkward, ungainly in our fumbling pursuit of his secret.

The large piece of plywood that forms a lean-to door to the camp is just ajar, behind is darkness. This, although a significant subject of our participants’ researches, is not permitted field research, not today. This camp and the larger shanty towns further along the canal are inhabited by unofficial populations of sans papiers, emerging from these chance amenities, on waste ground or here, under a periphery bridge by the canal.

As we cannot remain in a group in this half private territory and be ourselves unobserved, I have to abandon my subject of the solitary man and his washing. We must move on, with reluctance, leaving the thick cool of the bridge’s shelter for the glare of the path once more. The strong lights and shadow, the stillness of heat makes me think also of Daumier – his washerwomen performing that same task along the same river one hundred and fifty years before, the light and shade, the bridges, soft lit water, baskets underarm. Daumier and his emigrants; his destitutes, his people at the city’s edge.

As we cannot remain in a group in this half private territory and be ourselves unobserved, I have to abandon my subject of the solitary man and his washing. We must move on, with reluctance, leaving the thick cool of the bridge’s shelter for the glare of the path once more. The strong lights and shadow, the stillness of heat makes me think also of Daumier – his washerwomen performing that same task along the same river one hundred and fifty years before, the light and shade, the bridges, soft lit water, baskets underarm. Daumier and his emigrants; his destitutes, his people at the city’s edge.

We continue along the chalky path, now officially beyond the Périphérique and in the banlieue, and pause to regroup opposite an imposing configuration of buildings, with a tall white tower. There is a building to the right, not unlike one of Lowry’s Salford hulks, which used to house the flats of the laundry workers. I draw the tower while my friend relates the history of this site; the Elis laundry at Pantin was once the largest laundry in Paris, at the start of the Third Republic. Here came the bundles of fine linen sheets, thick tablecloths from hotels, restaurants and the grander private establishments. Day and night the cloth was boiled to remove the stains of bourgeois and ordinary vice; purged, starched and returned for new beginnings on ornate tables and bedrooms across the city. This laundry was performing on a vast scale for the ascendant powers of the city the everyday necessity of which the man in the shadows has just reminded us. Again this is a place where I would like to pause, although its scale somehow defies a drawn depiction, but we must keep walking.

It becomes quieter, we walk past a derelict, large graffitied building on the other side of the canal. The heat is intense, we have been walking for over three hours and people are tiring; drawing is giving way to digital snapping. It is almost time to turn off to our final destination in Bobigny.

It becomes quieter, we walk past a derelict, large graffitied building on the other side of the canal. The heat is intense, we have been walking for over three hours and people are tiring; drawing is giving way to digital snapping. It is almost time to turn off to our final destination in Bobigny.

I am wondering what sort of shape I can give to any of it, when I am caught short, suddenly, by a chance glimpse, across a perimeter fence, into a vast low building made from white corrugated metal containers. The doors are rolled back and I watch a procession of white sheets, pillowcases, draped from washing lines by metal clips, twitching a slow progress as they are pulled across a room in their diagonal festooning. The lines are stretched at angles into the far distance, the whole space filled with these slowly moving white hangings twitched along at gentle pace, a quiet jerky rhythm. Through the room move the laundry attendants, in clean uniform, the women’s hair bound back in white bandanas; they shift and adjust the laundry on the lines. I am transfixed by this oddly fantastical scene. It is a scene to feast on; the garlands of washing being pulled in continuous rhythm through the room. Outside in the fenced-off yard vans stand ready to take the newly laundered sheets and tablecloths to legions of identical Accor group hotels on the periphery, or in the centre. All the bodies at work in this scene of whiteness are black; and the afternoon in its immense heat only increases this stubborn marking of black white, cool shadow and sharp heat. It is the heat that has permitted this chance viewing, forcing the doors to be slid open for air with a view out to the canal. I feel as though everything else that we had paused at on the way – the solitary sans papiers at his private canal side washing, the disused municipal laundry complex further up, the heat and water, dark and light, the resistance of the hot afternoon, was leading to this last subject; the calm of a woman looking out as she performs her low paid labour, her black arms moving against the white common sheets that come from the hotels, the prisons, the dormitories, for washing and returning to hotels, prisons and dormitories across this city. I want to stay here with this stillness, this quiet rhythm of the sheets that move along their mechanized path, the people moving silently between them - the scene holds me in its elegant complexity; but the last of the group has now overtaken me and I must catch them up and lead them to the end of our walk.

Liza Dimbleby November 2013

Liza Dimbleby November 2013