Andrew Cranston: What to Do After a Death in Scotland, an exhibition at Hamish Morrison Galerie Berlin, November 2013.

An expanded version of this essay has been published in the book Andrew Cranston, Who Is This Who Is Coming? Aye-Aye Books, 2015. PDF of the full text available here

“Dreams are objective facts. They do not answer our expectations and we have not invented them”. (Wilfred Bion)

Each day we perform a precarious saunter from sleep to waking and from waking life to sleep. At the threshold there is always resistance; too sudden a transition is a shock. These are different worlds; and yet there is a continual daily traffic between the landscapes of our sleeping mind and our daily waking encounters. Images from dreams hover at the side of consciousness or ride before us as we field the relentless visual triggers of everyday life. Likewise the images we have taken in by day, in the street, in pictures or films, insist and reactivate themselves beyond our waking consciousness. The border is porous and we cannot build a resistant wall. Instead there is a continuous plunder; a shape-shifting and rearranging, eluding our designs.

The artist who makes this uneasy translation his work is himself subject to the transient and variant truths of what remains unseen. He too must overcome a stubborn resistance and give himself up to work, as to sleep. A tortoise drawn into its shell on a square patterned chaise longue, The Problem with Painting, reminds us of the slow game of image making, of the importance of surfaces.

The game is a strange complicity of consciousness and unconscious, distilled through time and through the media of paint, glass and dust, layers of varnish. The images that persist are those that keep returning. Another title, A Narrative Driven by Shape, refers to the way that shapes lead, prior to words or even outline. The humped bedclothes of Carl Spizweg’s “Poor Poet” painting resurface as icebergs. A boulder the painter once climbed recurs repeatedly, referring to Netherland landscape paintings, to the film Picnic at Hanging Rock, recalling a Beckett stage set, a huge cyst; a form that evokes boulder, cyst and anal sphincter in one, with women and parasols hovering above (in the painting 1900). This annus/anus image might also remind the Beckett conscious viewer not only of the writer’s stagings, but of his persistent problems with cysts, on his neck and memorably in his anus, for which he consulted the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, cited above. In other pictures the ovoid shape is a paint lid-ship’s funnel, a head of frizzy spectral hair.

Each day we perform a precarious saunter from sleep to waking and from waking life to sleep. At the threshold there is always resistance; too sudden a transition is a shock. These are different worlds; and yet there is a continual daily traffic between the landscapes of our sleeping mind and our daily waking encounters. Images from dreams hover at the side of consciousness or ride before us as we field the relentless visual triggers of everyday life. Likewise the images we have taken in by day, in the street, in pictures or films, insist and reactivate themselves beyond our waking consciousness. The border is porous and we cannot build a resistant wall. Instead there is a continuous plunder; a shape-shifting and rearranging, eluding our designs.

The artist who makes this uneasy translation his work is himself subject to the transient and variant truths of what remains unseen. He too must overcome a stubborn resistance and give himself up to work, as to sleep. A tortoise drawn into its shell on a square patterned chaise longue, The Problem with Painting, reminds us of the slow game of image making, of the importance of surfaces.

The game is a strange complicity of consciousness and unconscious, distilled through time and through the media of paint, glass and dust, layers of varnish. The images that persist are those that keep returning. Another title, A Narrative Driven by Shape, refers to the way that shapes lead, prior to words or even outline. The humped bedclothes of Carl Spizweg’s “Poor Poet” painting resurface as icebergs. A boulder the painter once climbed recurs repeatedly, referring to Netherland landscape paintings, to the film Picnic at Hanging Rock, recalling a Beckett stage set, a huge cyst; a form that evokes boulder, cyst and anal sphincter in one, with women and parasols hovering above (in the painting 1900). This annus/anus image might also remind the Beckett conscious viewer not only of the writer’s stagings, but of his persistent problems with cysts, on his neck and memorably in his anus, for which he consulted the psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, cited above. In other pictures the ovoid shape is a paint lid-ship’s funnel, a head of frizzy spectral hair.

In Hero, a flaccid figure sits slumped on top of a massive swollen shape - egg, world or rock. The body is forlorn, middle aged, tattooed across the shoulders the words REAL LIFE. The pathetic cipher that is our waking life sits just managing to keep on top of this vast excrescent boulder of paint and dirt and hairs and varnish. Varnish pools, seeps and bulges, catching dust and hair, yellowish smears; containing its detritus like a perverse amber, a pustulent cyst. This is the stuff from which paintings are made. This brute impenetrable mass is the whole mute indeterminacy of everything that remains hidden from us; the inchoate world we hardly fathom yet remain bound to. We can only hope to hold our ground; we are unable to escape it. We suspect it to be more powerful than us. Its half-deciphered contents remain suspended in the murky resistance of resin.

This stubborn materiality is evident also in the large painting I See a Darkness. The icebergs are themselves glass, shards in a black-oil varnish sea. Icebergs like bedclothes, like death, like separation. In After Fuseli, the slack and warp of sacking on which a mattress is painted yields to the paint as it does to the man painted lying on his bed; the sag of canvas is the sag of the mattress itself. A monkey hovers.

This stubborn materiality is evident also in the large painting I See a Darkness. The icebergs are themselves glass, shards in a black-oil varnish sea. Icebergs like bedclothes, like death, like separation. In After Fuseli, the slack and warp of sacking on which a mattress is painted yields to the paint as it does to the man painted lying on his bed; the sag of canvas is the sag of the mattress itself. A monkey hovers.

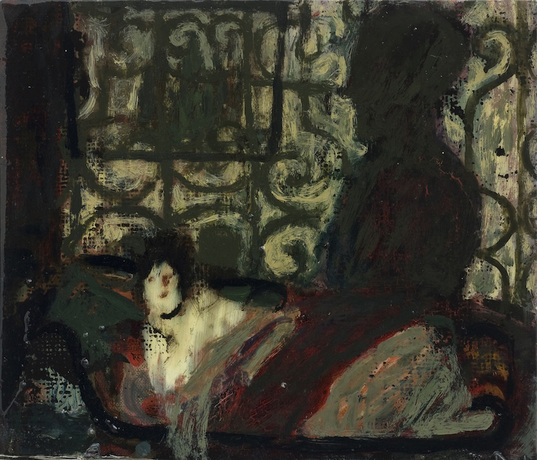

The shadow of a man, the after-images of Fuseli, Vuillard’s wallpaper, an early French “ambient horror” film still (Jacques Tourneur), dark lit rooms and the memory of end of century intimisme. After-images of things seen combined with that which surfaces. In this hybrid hinterland we are trying to look at things usually kept hidden. As for the intimistes, as for Beckett, the lighting is crucial to the staging. It is a night time world, warmly lit. The images that are encouraged to surface are sometimes taboo; sex, death, nightmares and the ultimate questions, not without a sly humour.

The wall is a recurring image. A wall that divides the imaginary space; a wall or canvas set in space, but also the wall that separates sleep and waking life, never absolutely. A wall that is as much a projection screen for the shadow lives of each consciousness in the other as it is a true separation. Something is always stirring on the other side of the wall.

To make and remake the thing; the materials are unpredictable but that is crucial in this game of hazard and incitement. The artist translates with wit from a world that is both intimate and estranged; he lies in wait for the stuff that might surface from the viscosity, from the almost impenetrable. He waits for something that might be recognised. Painting is perhaps the only way to ease the transition, to confront the wall.

Liza Dimbleby, Glasgow, November 2013

To make and remake the thing; the materials are unpredictable but that is crucial in this game of hazard and incitement. The artist translates with wit from a world that is both intimate and estranged; he lies in wait for the stuff that might surface from the viscosity, from the almost impenetrable. He waits for something that might be recognised. Painting is perhaps the only way to ease the transition, to confront the wall.

Liza Dimbleby, Glasgow, November 2013