CHAGALL'S BOX, exhibition at Tate Liverpool, October 2013

The importance of disruption. It is this that is necessary, says Paul, showing me his paintings. I am familiar with his argument. The simultaneity, discontinuity of worlds, inside, outside, colliding and rubbing up against each other. The paint must “incite” the other parts of painting. Perhaps in the way that the everyday “incites” the visions, the inner glimpses, ghosts and transformations. We live on the boundaries, the edges between the two, we draw from both and must continue to do so, if we are not to become dissipated. Without such porousness the world surrounding us is just mundanity, but without the summons of everyday life we would risk suffocation in the shadow world of inner fancies. It is a precarious balance.

In a café on Shoreditch high street we sit and talk, looking out through the windows at the figures sitting with their backs to us at the tables on the pavement. You can die when you are still in life, it happens, people die every day. They give up; says Paul. Look at them, the Dead Souls, a world of dead souls; you can die and keep walking.

Through the glass I am watching a girl, tiny skirt, bare skinny legs and platform heels, pacing back and forth on the pavement, swigging at a bottle of coke. A car with blacked out windows pulls up, and she gets in. People huddle along the pavement, mid-afternoon, often they stop to ask for a light, a cigarette even from those sitting at the tables. A hobbling couple move into the frame; she is pushing, or being held, by a large tartan trolley on wheels, they slow down in front of the empty tables, scour the ashtrays for cigarette butts, pick out the longest to put in their luggage and pass on. Dead Souls.

I was thinking of the Chagall etchings for Gogol’s prose poem, and how after long looking the faces of passers by seem to meld into the memories of his imagined images, the pitted, excised and caricatured phantasmagoria made solid with metal and ink; his strange parade.

I took the train to Liverpool for the last day of the Chagall exhibition; plunged past the pushing hoard of Sunday shoppers, the pound shops with life size cardboard cutouts of policemen and blurred posters of people caught red-handed displayed in their windows as though this was their wares. A vast pedestrian highway; as hostile to the walker as the band of motorway before you reach the docks. It is a relief to get to the museum. I head upstairs and sink in to works on paper, card and canvas.

In a café on Shoreditch high street we sit and talk, looking out through the windows at the figures sitting with their backs to us at the tables on the pavement. You can die when you are still in life, it happens, people die every day. They give up; says Paul. Look at them, the Dead Souls, a world of dead souls; you can die and keep walking.

Through the glass I am watching a girl, tiny skirt, bare skinny legs and platform heels, pacing back and forth on the pavement, swigging at a bottle of coke. A car with blacked out windows pulls up, and she gets in. People huddle along the pavement, mid-afternoon, often they stop to ask for a light, a cigarette even from those sitting at the tables. A hobbling couple move into the frame; she is pushing, or being held, by a large tartan trolley on wheels, they slow down in front of the empty tables, scour the ashtrays for cigarette butts, pick out the longest to put in their luggage and pass on. Dead Souls.

I was thinking of the Chagall etchings for Gogol’s prose poem, and how after long looking the faces of passers by seem to meld into the memories of his imagined images, the pitted, excised and caricatured phantasmagoria made solid with metal and ink; his strange parade.

I took the train to Liverpool for the last day of the Chagall exhibition; plunged past the pushing hoard of Sunday shoppers, the pound shops with life size cardboard cutouts of policemen and blurred posters of people caught red-handed displayed in their windows as though this was their wares. A vast pedestrian highway; as hostile to the walker as the band of motorway before you reach the docks. It is a relief to get to the museum. I head upstairs and sink in to works on paper, card and canvas.

There is the famous Poet at half past three with upturned head, the two headed homage to Apollinaire with gold and warm cardboard, I and the Village, Paris through the Window; all known but never yet seen. There are small village scenes painted in Paris, the first visit, with Tim Hyman smiling moons.I move anti clockwise through this wall of small windows from 1911 Paris to Vitebsk.

Then an actual window, the same scale but brighter, framing the sharp afternoon sun on the Mersey, Port sunlight. At this distance the harsh Sunday shopping Liverpool gives way to a picture of water and light. In the room the crowds are mostly groups of Orthodox Jews in skullcaps and wigs, some are being led on a guided tour by a rabbi. Now he is standing in front of Half Past Three (the Poet); two women are admiring the delicacy, translucency of the patterned curtain in the top right corner and I silently agree.

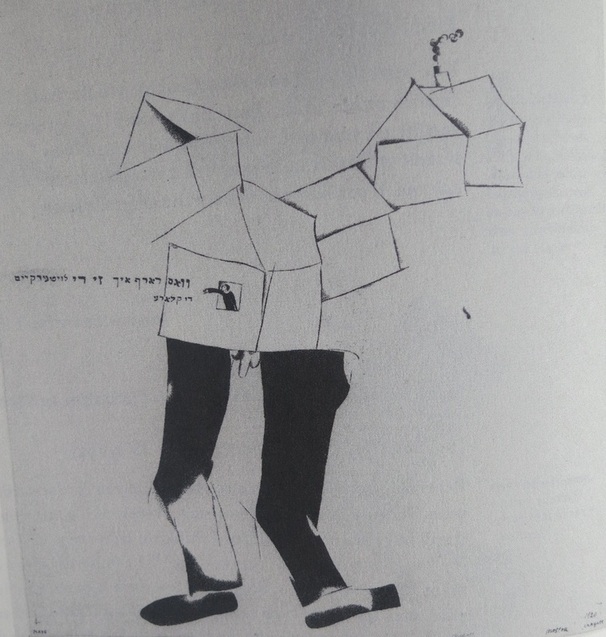

I move on through the displays “The Sense of Self and Jewish Themes” whose bearded figures are also those of the visitors looking at them, and on to the 1920s works on paper from the Pompidou Centre. Here are collages of paper and street and Cyrillic script. At the corner of the entrance to the next room is the Village Walking, familiar to me from books but never seen. I stop and look and stand back and look and listen to the conversations of those who stop at it, for many do. An old man, humorous eyes, long beard and skull cap sounds out the letters of the Yiddish (What use to me the clarity, the lucidity?) to his wife who nods and smiles, at the black walking legs and downward pointing penis balanced beneath precarious rooftops; from the window of an ink house head a man leans out and ejects his Yiddish lament from the poem of Mourning.

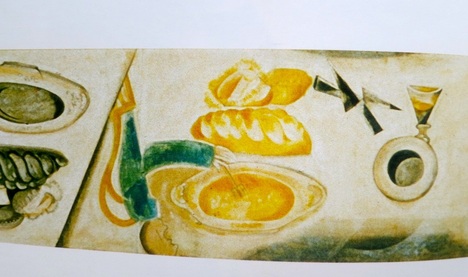

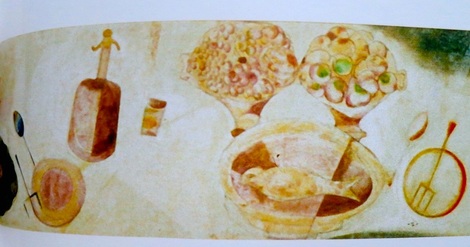

And then on into the finale. The murals for the Jewish Theatre, painted in 1920, in the hunger and chaos of civil war Moscow; four long panels, an 8 metre banner of a wedding feast up high and two vast walls you could almost walk into, but light and spacious in their water painted spaces. People called the ensemble “Chagall’s box” and now this room is Chagall’s box on sea, on the Mersey, set adrift from 1920s Moscow and beached up in 2013 Liverpool. The guests in the room are indeed guests at the wedding feast, their clothes and faces fit in and they are noisy, cheerful, greeting each other in Yiddish and English, meeting in family groups, three generations or more. There is a party mood and they stride to and forth across the room between friends and relations, or sit on the benches and spell out the Hebrew letters to each other. You stand and trace the dance, Chagall and palette, a monocled man in suit clasping another by the legs, the faces peering from behind the planes and curves and lines, flattened echoes of constructivism, but gentler; red and black giving way to pastelly paint and an absorbing sagey green. The short man with glass of tea, acrobats, musicians and goats. El Lissitsky bearing a tray of bowls and bottles on his head at the top edge, Malevich peeing on a pig at the bottom. A knife that looks that it might be spearing a pregnant belly but is in fact a circumcision. Emblems from Jewish history; Chagall, Tom Thumb size, lecturing from the leaf of a beanstalk.

Behind, the narrow panels that Kitaj repeated, framing the scribe, the fiddler, dancer and wedding joker. At the end wall, a strange grey-white insinuation of tresses in a ghostly post-constructivist graphic. Tantalising and perhaps most delighting is the long dinner table high above, with plates and trident forks, the soda siphons, tiny triangular vodka glasses, soup spilling out letters and a man upside down wound into his chair, eating; there are dishes full of fruit; grapes and pears, unplucked hens on a plate, fishes, even a boy on a plate.

Underneath, the party whirls, the cheerful excited buzz of North West England’s diaspora who continue these letters, these rituals, still distinct and mysterious to the outsider; they have a right to be here, to take their place in this box. The rest of us look at them as well as the murals, the whole thing.

I try to hold and fix it all in my mind to take it inside me, in its clarity, its surprisingness.

I try to hold and fix it all in my mind to take it inside me, in its clarity, its surprisingness.

Chagall’s box. A man abseils into the world, or rides the circumference of a world within world, snug behind a stage set hill, umbrella in hand, laughing at his own device. Playful cosmologies, large breasted curves you could jump between; playing hide in seek between worlds as the Chagall self does, an Alice in Wonderland leap of scale, Hebrew letters swirling like confetti; Chagall at play, discoursing, animating, setting history, friends, enemies and animals in motion to join the dance. The knives, the banner, the pears, the letters, the soup plates; the people laughing, greeting, talking, wondering, deciphering. Side by side on the benches; and from the window the Mersey, late afternoon sun and the ferry coming in.

Liza Dimbleby, Liverpool sketchbook, October 2013